126 million. The old adage says that there is strength in numbers, but in this case it is a sign of a global society that either cares too little or is not imaginative enough to explore new possibilities.

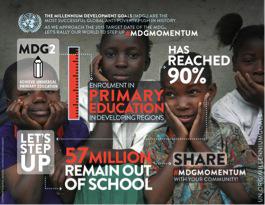

According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, in 2011 there were at least 126 million people of primary and lower secondary school age that were out-of-school. This staggering number has implications for developing and developed countries alike (although with varying severity). We all want children to have access to education because the benefits of education are very often linked to one’s happiness, self-confidence, the ability to more actively participate in one’s community, and increased job opportunities, among other things.

As we approach the 2015 deadline for achieving the Millennium Development Goals, the fact that for approximately 126 million children education will remain out of reach is all at once deplorable and cause to think outside of the box to address this issue. There is a general reluctance to try technology-based approaches that may help these children enter or make returns to education. Yet, despite the challenges involved, here’s why I think mobile technology can help.

First things first: The use of technology in education is not something that is new or innovative. Books, one of the oldest mobile technologies, have been around for ages. (I’m sure their initial integration into learning environments caused a stir, too!) Although mobile, books alone are not enough to reach learners who might not have access to education by attending school physically.

Distance education had its beginnings in the 1800s in the form of postal-based correspondence courses. This new form of education arose in response to the increase not only in people’s mobility but also because of movement into new areas where formal education institutions were not established or easily accessible.

Books and use of postal services to facilitate distance education were eventually complemented or supplanted by radio, TV, and of course desktop computers. In the developed world, distance education used to be viewed with much more skepticism than it is today because of questions about legitimacy, quality, and benefits to learners. As time has passed, distance education has gained more respect, and for many learners, including myself, it has often been the only option when time, money and/or geography have presented barriers to obtaining the education desired.

Increasingly, we are seeing mobile being used as a tool in distance education but, similar to all other technologies before it, there are choruses of naysayers that decry positioning mobile as a solution for out-of-school children. As well they should.

When it comes to helping 126 million out-of-school children access education, mobile, like all other technologies before it, is not the solution. It is an aid that must work in conjunction with out-of-school children, their parents, their communities and within their societies to help create educational opportunities where none exist.

But how can this be done?

Distance education as we know it has provided us with myriad examples of what’s possible. However, for newer technologies like mobile phones, an increasingly ubiquitous technology second only to radio in terms of people’s ability to access it in the developing world, there is not yet a well-worn path to follow, particularly at the primary and secondary levels. Further compounding the challenge is the perception that it is too difficult to learn with mobile phones because of limitations on screen size, technical functionality of the devices, users’ skills, and so on. Yet, based on my experiences in this area, I believe we are limited only by our imagination and our willingness to try something new.

My interest in using mobile to help facilitate access to education was first sparked during my time serving as a U.S. Peace Corps Volunteer in Madagascar (’08-’09). I worked with a teenage girl in my town that was out of school due to a lack of money and the need to help support her widowed father. Nevertheless, she had her own mobile phone. We practiced her English and my Malagasy skills via text messages. While a somewhat rudimentary way to access “education,” for us this became a vital medium for communication, for acquiring new vocabulary, and building fluency through experimentation with language in use – all at a distance.

So much of the dialogue among practitioners and policymakers on the use of mobile for education access has focused on what mobile phones can’t do, or how educators might be undermined if mobiles are used in/for education. Instead, I recommend taking a more optimistic approach to explore how functionality of even basic handsets can allow not just for content delivery but also for knowledge construction among and between peers and educators. While the aforementioned girl’s circumstances prevented her from physically attending school, letting 126 million boys and girls like her lose out on an education because of structural challenges they did not create would be even more disappointing.

Despite all of this, trailblazers in distance education and mobile learning in the Global South exist for people who would otherwise have no access – albeit at the tertiary level. For nearly five years the University of Colombo (Sri Lanka), in partnership with mobile network operator Mobitel, has offered graduate studies in business via mobile devices. The same program was launched in the Maldives in 2010 with Wataniya Telecom. These successful (and growing) programs were forged through multi-stakeholder collaborations that put the needs of people to have access to quality, accredited education at the heart of the efforts.

Elsewhere, a promising start to distance education and mobile learning was the memorandum of understanding signed between the African Virtual University and iHub Research in Kenya in 2012. Not only is this is important because it acknowledges that in Africa the reach of mobile services will likely always eclipse that of physical schools and fixed-line infrastructure, it also maps into the potential of creating new opportunities for education access that are locally designed and relevant.

So what about the 126 million out-of-school learners at the primary and secondary levels?

In the United States, so-called virtual high schools are bridging gaps for students who are physically unable to attend school, experience time constraints, or prefer home school environments. At present, however, most of these opportunities are PC-based. In South Africa, Dr Math offers mobile device-based tutoring services for young learners, but this is still not an avenue to receiving formal education so much as it is support for students who already have access. I believe that somewhere between these two approaches lies a model that can help children who are out-of-school access quality education on a consistent basis. A step in the right direction would be to figure out how a model informed by evidence-based, participatory research involving communities, governments, civil society organizations, and the private sector could work.

What do I recommend?

As most anyone will caution you, a one-size-fits-all approach cannot be taken to address the critical issue of out-of-school children, but for countries where fixed-line and school infrastructure is lacking mobile learning represents some opportunities. Here is where I think the work can begin:

– Ask the out-of-school children what they need. Work with them to understand what their desired educational outcomes are and how they might be facilitated. I don’t believe enough of this dialogue has taken place.

– Forge multi-stakeholder partnerships of organizations and people that are broadly interested in and/or committed to realizing the potential of mobile use in education. These coalitions should include representatives from among the out-of-school children.

– Stakeholders should collaboratively examine and act upon the areas that mobile can make contributions where fixed and PC-based services cannot. In many respects, practical implementations of mobile learning initiatives for out-of-school children are relatively few and nascent. Yet, a growing evidence base exists that people can draw from. Don’t reinvent the wheel!

– Stop focusing on what mobile can’t help people do and instead work with what it can. As mentioned earlier, there are still ways that even basic handsets can facilitate knowledge construction among geographically dispersed learners.

– Fear of technology and associated power dynamics between parents, teachers and learners must be overcome if mobile learning to reach out-of-school children is to have a chance to make an impact.While we must always be vigilant of any negative effects mobile learning for out-of-school children and their communities might create, these possibilities alone are not sufficient reason not to work towards this opportunity.

Right now we are leaving children behind. So when will we realize that out-of-school does not have to mean out of reach? While use of mobile undoubtedly has its challenges in providing access to education, we would be hard pressed to find a child among the 126 million who does not think it is at least worth a try.

Interested in working together to see how mobile can help provide access to quality education? Share your thoughts with me at @GLaM_Leo on Twitter or by visiting my website at www.rondazg.com.