Many have addressed how present and future students should learn. Few have examined what students should learn for the 21st century.

The rapid increase in the rate of systemic change around the globe creates an increasingly volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous world and thus is significantly more unpredictable. Six emerging trends will require a diverse set of individual abilities and competencies and an increased collaboration among cultures.

The average human lifespan is lengthening and will produce collective changes in societal dynamics, including better institutional memory and more intergenerational interactions. It will also bring about increased resistance to change. This may also lead to economic implications, such as multiple careers over one’s lifespan and conflicts over resource allocation between younger and older generations. Such a context will require intergenerational sensitivity and a collective systems mindset in which each person balances his or her personal and societal needs.

The rapid increase in the world’s interconnectedness has had many compounding effects, including exponential increase in the velocity of the dissemination of information and ideas, with more complex interactions on a global basis. Information processing has already had profound effects on how we work and think. It also brings with it increased concerns and issues about data ownership, trust, and the overall attention to and reorganization of present societal structures. Thriving in this context will require tolerance of a diversity of cultures, practices, and world views, as well as the ability to leverage this connectedness.

Along with our many unprecedented technological advances, human society is using up our environment at an unprecedented rate, consuming more of it and throwing more of it away. So far, our technologies have wrung from nature an extraordinary bounty of food, oil, and materials. Scientists calculate that humans use approximately “40 percent of potential terrestrial [plant] production” for themselves (Global Change, 2008). What’s more, we have been mining the remains of plants and animals from hundreds of millions of years ago in the form of fossil fuels in the relatively short period of a few centuries. Without technology, we would have no chance of supporting a population of one billion people, much less seven billion and climbing.

While the creation of new technologies always leads to changes in a society, the increasing development and diffusion of smart machines—that is, technologies that can perform tasks once considered only executable by humans—has led to increased automation and offshorability of jobs and production of goods. In turn, this shift creates dramatic changes in the workforce and in overall economic instability, with uneven employment. At the same time, it pushes us toward overdependence on technology—potentially decreasing individual resourcefulness. These shifts have placed an emphasis on non-automatable skills (such as synthesis and creativity), along with a move toward a do-it-yourself (DIY) maker economy and a proactive human-technology balance (that is, one that permits us to choose what, when, and how to rely on technology).

The influx of digital technologies and new media has allowed for a generation of “big data” and brings with it tremendous advantages and concerns. Massive data sets generated by millions of individuals afford us the ability to leverage those data for the creation of simulations and models, allowing for deeper understanding of human behavioral pat- terns, and ultimately for evidence-based decision making.

Advances in prosthetic, genetic, and pharmacological supports are redefining human capabilities while blurring the lines between disability and enhancement. These changes have the potential to create “amplified humans.” At the same time, increasing innovation in virtual reality may lead to confusion regarding real versus virtual and what can be trusted. Such a merging shift of natural and technological requires us to re conceptualize what it means to be human with technological augmentations and refocus on the real world, not just the digital world.

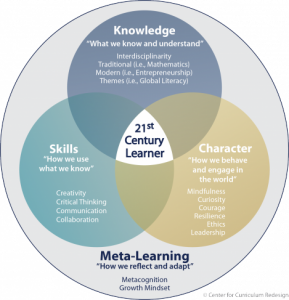

All of these changes discussed above highlight why it is so critical to rethink the What of a 21st century education. Curricula worldwide have often been tweaked, but they have never been completely redesigned for the comprehensive education of Knowledge, Skills, Character, and Meta-learning— the four dimensions of education defined by the Center for Curriculum Redesign.

In a rapidly changing world, it is easy to get focused on current requirements, needs, and demands. Yet, adequately preparing for the future means actively creating it: the future is not the inevitable or something we are pulled into. There is a feedback loop between what the future could be and what we want it to be, and we have to deliberately choose to construct the reality we wish to experience. We may see global trends and their effects creating the ever-present future on the horizon, but it is up to us to choose to actively engage in co-constructing that future.

Charles Fadel is Founder of the Center for Curriculum Redesign and co-author of the upcoming book: “Four-Dimensional Education”.