Nestled inside a bamboo forest, Supo Elementary School was founded in 1917, and for decades was considered the best school in the lush rural outskirts of Chengdu, the mega-city capital of Sichuan province. That’s to say that rural children recited texts under their voices became coarse, and did test questions until their eyes squinted.

In the eighties, the golden wheat fields that surrounded Supo started to empty out, as the young flocked to the cities to toil in factories. In the nineties, history’s biggest human migration gave way to history’s largest urban sprawl. Chengdu swallowed whole its surrounding countryside by pouring concrete over fields and meadows, and over two decades it tripled in area, and quintupled in population to over ten million. To sustain its growth, Chengdu had to figure out how to turn landless farmers into knowledge workers. That meant turning around rural schools, and ground zero in this attempt was Supo Elementary School.

At first, that meant bringing in experts to stir the complacent calm at Supo, but over time Chengdu became radically ambitious. Promoting equity and creativity in its school system became Chengdu’s top priority, and it poured money, resources, and talent into its suburbs as it had once poured concrete to make them. It promised pay and promotion to those who would come, and it scoured its top inner city schools for talent.

And the man who Chengdu picked to turn around Supo just happened to be a man the city had previously thought too dangerous to put into power.

***

After the Communist Party clamped down on the 1989 student protests, it decided to teach China’s best and brightest a lesson by exiling them to teach in the poor countryside. But the exiles were more intent on democracy than on pedagogy, and they brought their revolution into some of China’s poorest schools. One of their students happened to be short, shy, and not at all studious who found himself a cadre by accident. His name was Li Yong, and the democracy experiment he stumbled upon changed his destiny. Winning elections and organizing activities made him articulate and confident. He found inspiration in his teachers, and he became one so that he could be an intellectual idealist like them.

In 2004, after a decade of teaching in the countryside, Li Yong won a provincial teaching competition, and Sichuan’s best elementary school plucked him from obscurity. When Li Yong arrived at Chengdu Experimental Elementary School, he blanched at the school’s military-like focus on obedience and discipline. He taught his fifth and sixth graders how to analyze and criticize the textbooks they were meant to memorize as gospel, and ditched his colleagues for dissidents. Li Yong was brilliant and dynamic in the classroom, and the school administrators decided that’s where he must stay for his entire career. Li Yong blogged his scorn, and soon his office colleagues scolded him: “If you think our school sucks, why don’t you start your own school?”

Then Li Yong had a thought: Well, why shouldn’t I?

***

In Chengdu’s search for young talent to ship to the suburbs, Li Yong made the final cut after a rigorous series of tests and interviews. When Chengdu education officials went into Li Yong’s school to do a background check, everyone described Li Yong (including himself) as a fenqing, which translates literally as “an angry young man” but really means “an unrepentant troublemaker.”

The officials decided to take a chance on Li Yong. The Chengdu government prided itself on being open and bold, an attitude that had made the city the most economically competitive in China.

In 2008 Chengdu tasked Li Yong with building his own primary school in the suburbs. He was determined to make it work, and prove himself. He wrote a letter to parents every week, demanded his teachers write him a weekly letter, and soon enough demanded they write weekly to parents as well. Whenever teachers made their students stay in class during lunch hour to do homework, Li Yong stood outside the door until the kids were set free. He audited classes, and when he saw kids dozing off he took over the podium. Li Yong found one math teacher’s classroom manners so disappointing that he spent a week sitting in the back of his class. That math teacher also happened to be his best friend who drove him to and from work everyday.

Li Yong’s drive and tenacity didn’t create the most pleasant work environment, but he produced results. Students were happy that they had playtime, parents were grateful their child’s test scores went up, and teachers became loyal converts after they won teaching competitions. Li Yong produced such impressive results that Chengdu’s education officials tapped him for their most ambitious project to date: a school that would showcase the government’s commitment to equity and creativity. The new school – Tonghui – would absorb the conservative Supo Elementary School while blending in a special education program for autistic children.

Tonghui was meant to show how helping society’s neediest would both teach tolerance and drive creativity. It was a bold vision, but no one had put much thought into the practicalities. Faced with a faculty more hard-headed than him, Li Yong regretted taking the job from day one. To build a school, he needed passion and will. To transform a school, he realized he needed forbearance and humility.

In other words, Li Yong needed to change himself first before he could transform Supo. But where in the world could he find the strength to change?

***

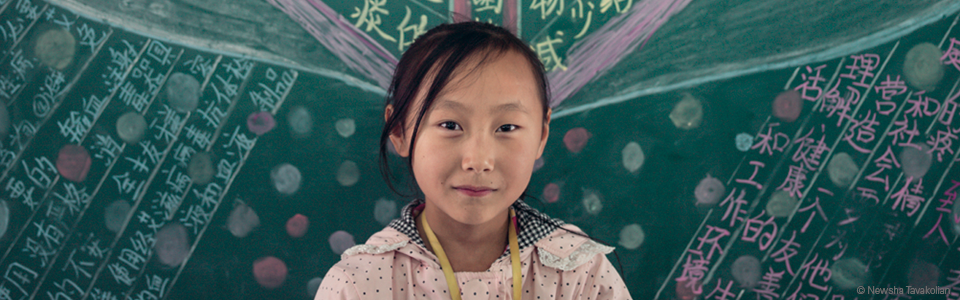

In mid-December 2015, I traveled to Chengdu to see if Li Yong had succeeded in turning around Tonghui, and if so how. By government metrics, Li Yong had succeeded – the school was a creativity hotbed, teachers were more satisfied with their work, and the school had an award-winning arts and sports program. But I wanted to know if Tonghui provided students with a 21st century education, and so I designed a questionnaire to see if the students had a “growth” or “fixed” mindset, and if they were driven intrinsically or extrinsically. I conducted surveys and focus groups, and to my pleasant surprise the students knew that to succeed, they had to discover, follow, and persist in their passion.

One example of Tonghui’s creativity was its forty self-organized student clubs, and I spent one afternoon watching the members of a theater group rehearsing on the school’s lush verdant rooftop. The girls did what little girls do, and they ran around a sandbox, and squealed. The director sat calm and confident on a bench, and let the girls exhaust themselves before marshaling them back to rehearsal. She was so mature that I only remembered she was a sixth-grader when I asked her how organizing her own club was developing her intellectually, and she blinked her large brown eyes at me, twirled her long silky black hair with her finger, and muttered, “Huh?” After a long chat, I discovered how purpose and responsibility had strengthened her academic focus, emotional resilience, and imagination in the same way that they had made Li Yong articulate and confident when he was a student cadre. She was an average student who fought with her strict parents in public, but after a semester of running her own club she become serious about school, kept cool around her parents, and had been inspired by her squealing actors to write seven plays.

I had planned on spending a week at Tonghui, but I was so impressed that I spent three to figure out how Li Yong turned Tonghui around from one of Chengdu’s most conservative to one of its most creative.

***

In any school transformation, there are three forces that need to be managed and balanced: information, power, and emotions. In the school reform architecture, information flow can be represented by windows and doors, power distribution by walls and floor plans, and emotional energies by the wiring and the plumbing. It is the emotional plumbing that determines how everyone in the school behaves and interacts with each other, and as such it’s a school’s emotional plumbing that determines if the reform process lives or sinks. And Tonghui built its emotional plumbing with laughter, love, and leadership.

Laughter

Every Sunday morning, Tonghui invites parents to take classes with their kids, and I spent one morning watching as parents and their kids took classes in safety and rescue, cooking, carpentry, and pottery. That whole morning, everyone couldn’t stop laughing as the parents bear-hugged their kids to safety from a make-believe burning building. I did not think that anyone learned anything that morning, but I was sure that after a morning of laughing together everyone felt closer to each other.

There are ample scientific studies showing how laughter builds people’s confidence, concentration, and creativity, while boosting their immunity, optimism, and sense of well-being. It also bonds people to each other, and creates a strong sense of community.

People laugh in a school that makes a point of reducing test stress, and encouraging interaction. When kids play together, they laugh together. Most important, laughter is infinite and infectious. At Tonghui, as children laughed in the hallways, teachers smiled at each other in the meeting rooms. The crisp laughter was so pleasantly pervasive I felt so calm and happy the whole time I was there.

Love

Miss Gao is a middle-aged teacher of sixth grade Chinese language and literature, and has a dark brooding face. In her classroom, I observed how an autistic student named Fanguo sat at the back of the class, and his square large body fidgeted about, behavior that would immediately draw ire from teachers.

But during the whole class Miss Gao just smiled at Fanguo, and she had a classroom calm that was such a contrast to her meeting room intensity. When she asked her sixth graders how they thought peach blossoms smelled, Fanguo raised his right hand, and stammered out in staccato Chinese, “Terrible – because I’m allergic to it, and it makes me sneeze.” Then Fanguo sneezed. The class laughed, and Miss Gao looked at Fanguo with a shine in her eyes. Later on, Miss Gao asked Fanguo to recite a poem, and he closed his eyes, and did so. The other 49 sixth graders knew that Miss Gao paid special attention to Fanguo, but they didn’t mind because it made the class more lively and relaxed.

After class, Miss Gao told me that she had been teaching Fanguo for two years now, and he forced her to change the way she managed her classroom. She told me that Fanguo had difficulty paying attention, liked to express himself, and had his own learning trajectory (in other words, Fanguo was less like an obedient Chinese student and more like a typical Western student). In response, Miss Gao had to make radical changes to her teaching style (like not getting angry). She smiled, and told me – with a mother’s pride in her voice – how during recess Fanguo liked to go out to the parking lot, and just stare at car lights. Also, Fanguo was the best in the class in math, English, and Chinese.

Miss Gao was one of the strictest teachers at Supo, and initially she was not a supporter of Li Yong’s reforms. All her life she believed that if students got low test scores it was because they didn’t work hard enough. When she was sent Fanguo and told he needed special care because he was autistic, her protective maternal instincts took over, and today she’s one of the teachers most actively calling for pedagogical reform.

From the perspective of neuroplasticity, this makes sense. The adult brain is less plastic than the adolescent brain, but the adult brain once again becomes capable of fast learning when we get married, and when we have children. In other words, people change when they deeply care about others.

While laughter and love had made reform possible at Tonghui, neither would have been possible without a leader who had the courage and humility to trust others, and the strength and faith to believe in everyone.

In other words, Tonghui’s transformation won’t have been possible without the transformation of Li Yong.

Leadership

Li Yong is forty-four years old, and has thick furrowed eyebrows. He has the thick calloused hands that speak of strong peasant stock. He has a short sturdy build he maintains by shooting hoops with gym teachers half his age, and a baritone voice he sharpens in his church choir. Once a proud contrarian and a fierce individualist, Li Yong was baptized as a Christian a few months after he joined Tonghui.

I attended Christmas Eve mass with Li Yong at his “underground” church, which occupied the fourth floor of a hotel. The room was packed that evening, and Li Yong huddled with the masses of Chengdu, dozens of the middle-aged and elderly who looked like Tonghui’s cooks and janitors. (Li Yong sat at the front, and because I was afraid I’d be discovered as a non-believer I hid out in the back.) That evening, everyone was equal, as a woman preacher with a deep sonorous voice told her congregation to open their hearts. Your greatest enemy will fall to his knees in submission, she told everyone, if you always turn your other cheek.

Li Yong couldn’t find the strength to change in this world, so he turned to God, and that Christmas Eve I could at least see how Li Yong changed Tonghui.

For most of his life, Li Yong was a fenqing desperate to change the world in his image, and his rage and anger compelled him to build a great primary school. It was religion that helped free him from his rage and anger, and armored him with the empathy and humility to transform Tonghui.

During Tonghui’s first two years, Li Yong sat patiently at reform meetings in which faculty heatedly argued back and forth. Miss Gao told me how she went into meetings at first determined to oppose reform, but after many faculty reform meetings she decided it was less of a bother to not oppose reform. By turning his other cheek, Li Yong simply exhausted everyone.

There was also how religion shifted Li Yong’s attention from the nuances of the classroom and upping test scores to the matters of soul and building a community. All religions are proto-school systems, and through religion Li Yong was re-learning those eternal truths that got replaced by statistics.

It’s humanly impossible to keep your ego in check when you’re the supreme authority over a playground, and in his church – where Li Yong surrounds himself with the meek and weak of society, and where he volunteers once a week as a lowly accountant – he was tempering himself with humility. And in so doing he learned to trust his students to start their own clubs, to give space to Miss Gao to turn around herself, and to have faith that the love of others will always conquer the habits of old.

Jiang Xueqin is a China-based writer and educator. He tweets at @xueqinjiang.

Jiang Xueqin was a speaker at WISE 2014. Watch his session: Empowering Teachers for Creativity.

Read the other articles in the series: Are Creativity and Innovation Possible in Chinese Schools; How Chengdu Schools Do Innovation; The China Education Debate: Equity Versus Excellence; The Pioneer Way: Emotional Scaffolding; The Xingwei Experiment