The growth of private education in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has sparked robust debate about the private sector’s place as an education provider. In light of this debate, it is important to explore how governments—guardians of their countries’ education systems—can choose to encourage and regulate private sector participation.

In what follows we explore the tools governments can leverage, drawing upon our learnings from The Business of Education in Africa, a major report we launched at World Economic Forum on Africa this year.

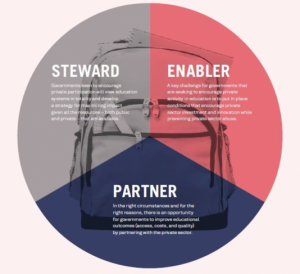

The Roles of Governments in Private Education

The government performs three key roles in relation to the private education sector: steward, enabler, and partner.

Steward

Governments act as stewards by carrying out a variety of functions. First, governments can improve the overall ecosystem for doing business – this includes cleaning up corruption and removing bureaucratic red tape. Governments can also confront inefficiencies by streamlining education governance. Another critical function of government as a steward is setting and enforcing standards. Lastly, policymakers can establish regulatory frameworks to govern the non-formal sector. Developing regulatory frameworks, like the new APBET guidelines in Kenya for non-formal K-12 schools, would help to eliminate a “grey market” in education and ensure that these essential education providers are properly managed and monitored.

Enabler

As an enabler, governments ensure that policy on private education, both for-profit and not-for-profit, is transparent and enables effective private participation, through regulations on 1) licensing; 2) operations; and 3) finance and investment. Governments can improve the enabling environment for private education by taking steps in these areas:

- Licensing: Governments can modify licensing requirements to reflect a diversity in potential provision (for example, changing land requirements to facilitate the entry of smaller urban university campuses). Standardized regulations can eliminate the influence of individual personalities and relationships on the licensing process. Governments can also facilitate expansion for operators by reducing the duration and complexity of licensing for branch campuses.

- Operations: Options for governments include reducing transaction costs for educational products and services (e.g. through eliminating taxes on products like textbooks). Governments can introduce concessions and incentives (like those observed, for example, in Dubai International Academic City) that incentivize participation in the education sector.

- Finance and investment: Policymakers should consider removing limitations on private provision across education segments (for example, private participation is not allowed in Ethiopia’s under-served teacher training segment), by allowing FDI and profit repatriation within the education sector, and by improving the availability of institutional and student finance through introducing credit facilities targeted at the education sector.

Partner

As partners, governments can consider public-private partnerships (PPPs) to expand quality and access. There are essentially three types of PPPs in education: 1) service delivery; 2) infrastructure development; and 3) service procurement:

- Delivery PPP models, in which government relies on the private sector to directly provide education, include the following:

- Governments can outsource school management to private operators; an example of this is Partnership Schools for Liberia, where private operators such as Bridge International Academies are managing education delivery in Liberian schools.

- Policymakers can also support education delivery through funding for private providers via vouchers, subsidies, and bonds.

- It is also recommended that governments promote and take advantage of innovative education solutions that the private sector offers. For example, funds such as the $1 billion i3 Fund in the USA support governments to identify and scale promising innovations in the private sector without experimenting in public sector schools.

- Developing infrastructure for education enables private providers to improve provision building, accessing, and/or managing public facilities, including:

- Drawing on the private sector to build and/or manage public education facilities, much like Africa Integras does for University of Ghana and Kenyatta University.

- Share public facilities with private providers to offer much-needed services.

- Procuring services from private providers allows governments to tap into the efficiency and delivery capabilities of the private sector, including:

- Partnering on teacher training programs, given the shortage of teachers across the continent. For example, the N-Power Teach Program is a two-year paid “volunteership” in Nigeria in partnership with private companies that aims to train 500,000 graduates as teachers.

- Procuring services and filling gaps in education system supply across segments, including language learning, edtech, data systems, and learning systems. For example, Green Shoots in South Africa is a not-for-profit/social enterprise hybrid providing online learning resources to more than 55,000 children in about 100 public schools.

Policymakers will play the key role in ensuring that SSA’s unparalleled demographic growth will yield a positive dividend. This demands that future generations of Africans be provided the skills required for a globalized world. Involving and leveraging the private education sector can only help. This is not without its challenges: policymakers face resistance from a range of actors, concerns from teachers (unionized and otherwise), reluctance from the private sector to engage with government, and broad diversity and fragmentation of the sector. Despite these challenges, it is both important and probable that the coming years SSA will see closer partnership between governments and the private sector as they jointly strive to improve the quality, access, and relevance of education.

This article is the third in a series on the current role and potential for private education in sub-Saharan Africa. The articles draw extensively on the authors’ work on The Business of Education in Africa, a report commissioned by Caerus Capital and supported by Parthenon-EY’s Education Centre of Excellence and Oxford Analytica. Priyanka Thapar, Emerging Markets Education Associate at Parthenon-EY, contributed to this article.