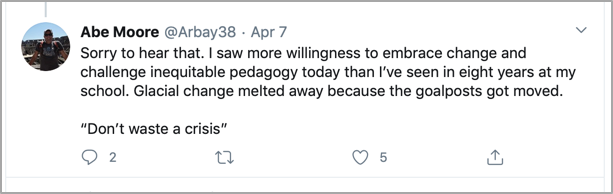

“Don’t waste a crisis”.

I’ve heard this statement many times during the COVID-19 months.

To me, this means thinking about how we work with new worldviews about teaching and learning, having had the rug pulled out from under us.

If deep learning requires an emotional shock/trigger, then having our daily behavioral patterns, habits and routines blown apart could be just what was needed to see our students anew, to know them as learners for the first time.

It has often been said that the greatest barrier to changing schooling has been the universal experience of it—a transactional, unspoken contract between teacher and student, of transmission and receipt of information. A transaction so common, it’s difficult to reimagine, to unlearn, to change.

In South Australia [SA] between 2010 and 2013, we learned how deeply held this unconscious contract was. A four-year classroom-based research project, involving 484 teachers, the ‘Communities Making a Difference National Partnerships: SA Teaching for Effective Learning [TfEL] Pedagogy Research Project’ revealed the complex inter-relationship at play between teachers’ pedagogy, learner engagement and achievement.

The research findings related to:

- Teachers’ observed pedagogical repertoire

- The relationship between teachers’ worldviews and the quality of pedagogy

- Baseline student characteristics and the impact of these characteristics on student engagement and achievement

- The relationship of quality of pedagogy and specific Teaching for Effective Learning (TfEL) elements on student characteristics—disposition to learn, interest, positive affect, negative affect and negative social functioning

- Student perceptions of teachers’ pedagogy.

Insights gleaned from this research identified increased student agency in learning as a key driver for, and outcome of the pedagogic change needed to improve statewide academic achievement.

This then became a focal point for a number of departmental initiatives at the time. One of these was the SA TfEL Pilot.

The SA TfEL Pilot was a partnership between the department’s Teaching and Learning Services and 10 schools willing to explore innovative ways to develop student agency in learning. The central principle of the initiative was that the participating school leaders and teachers would partner with students from scratch. This would not be consultation with students, but a genuine, generative design partnership.

Why was this the non-negotiable principle of the TfEL Pilot?

The answer lay in the research findings related to teachers’ worldviews and the quality of pedagogy. We were looking for ways to support teachers in developing their pedagogic repertoire that enabled learners to develop stronger learning dispositions and resilience in the face of complex, unfamiliar, non-routine learning challenges.

At that time however, 2000+ hours of classroom observation revealed a culture of ‘relationship-rescue’ where learners often were engaged in enjoyable activities with little cognitive demand. Our teachers worked hard, designed great activities, and cared for their learners, but the unintended outcome had become a culture of ‘rescuing’ them from doing the hard thinking. The interviews revealed significant ‘under-expectation’ of our students. This was a complex interplay of teacher beliefs, pedagogy and resultant student learning characteristics. The research showed that:

Key finding 1:

Teachers’ beliefs and assumptions about their role have an impact on their practice. Three orientations to practice were identified:

- content coverage and control: the teacher’s role is to cover the curriculum

- high relationship—low challenge: the teacher’s role is to care for the students

- responsive—learning and student-centred pedagogy: the teacher’s role is to ensure learners learn meaningfully.

Key finding 2:

Teachers’ epistemic awareness has an impact on their approach to teaching a ‘teaching as script’ approach, which places emphasis on a controlled, sequential progression and following a pre-planned approach, and a ‘teaching as design’ approach, which is characterised by a responsive, personalised approach to learners’ needs in order to achieve desired learning outcomes.

Key finding 3:

Teachers who have a ‘teaching as design’ approach demonstrated a more highly developed pedagogical repertoire.

Making visible the ‘under-expectation’ of our learners was key to changing practice towards a more responsive, highly developed pedagogic repertoire.

Hence the core principle of the TfEL Pilot.

If teachers and leaders authentically partnered with students to design new ways of working, they could see what they brought to the table, they could see them anew.

The pilot schools did this in a number of ways, these are just some.

- Craigmore High School set up the ‘5 x 5’ – a new form of PLC at their school. 5 students and 5 teachers designing units of work and seeking feedback from the students about redesigning for engagement and stretch.

- At Seaview High School, teachers developed ‘un-google-able questions’ for their subjects with students to ratchet up the degree of thinking challenge.

- At Gilles Street Primary school, students provided feedback to teachers about what did and didn’t work for them as learners of mathematics, with teachers subsequently sharing their plans as to how they would respond to the feedback.

- At the Marion Coast Partnership of Schools [EY to Yr 12] students and teachers designed the Student Learning Rounds where students observed in classrooms to gather examples of stretch thinking and ways of getting ‘unstuck’ in learning – then sharing these insights with teachers and leaders at staff meetings and parents at governing councils, with teachers adopting and adapting practices from colleagues that students found effective.

We learned that changing practice is hard.

We also learned that to shift from a ‘coverage’ transactional approach and begin to build a more dialogic, student centered pedagogy, teachers needed an epistemic ‘jolt’ and to see their students anew—as constructors of meaning, as bringers of ideas, and knowledge and experience…Only then was it possible to see that the prevailing transmissive pedagogy of coverage rendered their learners invisible, allowing no opportunity for them to develop agency and power in their learning.

We needed to make space. When the TfEL Pilot schools made this space through their co-designs, for many, the blinkers that made their students invisible started to fracture.

I wonder…Will the context of COVID-19 and the ‘jolt’ of losing the transmissive classroom routine and having to rethink our learning designs have been enough disruption for teachers to see their students anew and to value making space for them where agency can grow?