This tenth ASER is in a way a summary of what we have observed over the tenures of UPA I and II. It is also a baseline for the new government and what it has to deal with.

So, what did happen over the last 10 years? Parliament had unanimously passed the constitutional amendment to make education a fundamental right under the NDA government. The government changed in 2004 and one of the first steps taken by the new Prime Minister was to declare the imposition of a 2 percent cess to raise additional funds for elementary education. Subsequently a non-lapsable Prarambhik Shiksha Kosh was created to ensure that the income from the cess did not get used for anything but elementary education. The Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) that had started under NDA was continued with substantial increases in funding every year as the income from the cess grew with the increasing wealth in India. Although there were many competing demands from other social sector schemes, the funds available for elementary education increased substantially.

In 2005, when the first ASER survey was conducted, 93.4 percent of 6 to 14 year olds were found to be enrolled in schools. The 2005 ASER also reported that the proportion of Std 4 children who could read a Std 2 text was 47 percent.

Looking at those figures it seemed pretty clear to us that improving basic learning achievements in reading, writing, and math was the main big challenge before India. There was no disagreement about improving the quality of learning but the question was how. The education establishment led by NCERT rejected our assessment method and our suggestions for improving basic learning achievement as minimalist. Its own holistic National Curriculum Framework (NCF) was ready and from here on the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD) left the quality aspects to the NCERT while the administration itself focused its annual work plans on building schools, hiring teachers and creating other facilities.

NCF2005 did not go too far beyond the creation of textbooks, although it must be admitted they are good. A Reading Cell created within NCERT made no impact on children’s reading in any state and year after year ASER kept on reporting that basic learning levels were low. Just when it seemed as if the ASER results were getting repetitive, the Right to Education Act was passed (in 2009) and suddenly things began to change. In ASER 2010 we first noticed that the proportion of children in private schools was growing and learning levels had begun to decline. But officially the MHRD neither recognized ASER nor did it accept its findings as far as learning levels were concerned. Over the last two years it has been claiming that learning levels have improved marginally although they are low.

Well into the second decade of this century, the MHRD did not really take an interest in learning achievements. Its sole focus was on provisions, inputs and infrastructure. The thinking seemed implicitly linear; first all, infrastructure needs have to be taken care of and then quality issues can be addressed. Unfortunately, in states where infrastructure issues were not severe, there too states followed the MHRD cue and did nothing significant about basic learning levels.

It is quite clear that the SSA was really designed to take care of infrastructure and little else. How far did the strategy of focusing on infrastructure succeed in its goals?

On November 24, 2014, Mr. C.P. Narayanan, Member of Parliament, Rajya Sabha, asked a set of questions. The first three out of five were: “(a) whether all the children in the age group of 6 to 14 years in the country are enrolled in schools; (b) how many of them are able to avail free educational facilities extended by Government; (c) whether there are sufficient Government schools in all the States to cater to them”.

The response from the Minister for Human Resource Development is recorded as, “The census 2011 estimated 20.78 crore children in the 6-13 age group. In 2013-14 enrolment in elementary schools was 19.89 crore children in 14.49 lakh elementary schools, including 13.79 lakh government and government aided schools providing free education.” Clearly, the government has avoided answering part (b) specifically and implied that children in 13.79 lakh or 95 percent of the schools are getting free education. But, it appears that the number 13.79 lakh government and aided schools is incorrect. According to the government’s own DISE 2013-14, the number would be 10.94 lakh government schools + 60,000 aided schools, or about 11.5 lakh schools run or aided by governments.

The correct answer, based on DISE 2013-14, to sub-question (b) would be that out of 19.89 crore children enrolled in elementary schools, 12.1 crore were in government schools and 1.1 crore in aided schools. Thus 13.2 crore children receive free education and the remaining approximately 6.7 crore (34 percent) children, rich or poor, pay for their education (of these about 47 lakh go to unrecognized schools).

The private sector is no more just a small group of education providers. According to DISE, 39 percent of India’s urban and rural children go to private schools (ASER 2014 estimates that 31 percent of rural children go to private schools) including government-aided schools. If you add to this number government school children who go to private tutors, especially in the eastern states of India, the proportion of children accessing private schooling or tutoring inputs will rise to just under 50 percent.

Many Members of Parliament have been raising questions about schooling and education. The responses from the government often do not present a picture that will make sense in the spirit of the question. Perhaps it is time the government came out with a full statement about what it perceives as the four or five key issues in elementary education and how it expects to address them.

Responding to another question in Lok Sabha on November 26, 2014 from Mr. Kinjarapu Ram Mohan Naidu and others about plans to provide schools, the government said that it has sanctioned 2.04 lakh primary schools and 1.59 lakh upper primary schools around the country since 2002. Published DISE results say that until October 2013, 1.62 lakh primary schools and 77,000 upper primary schools have been built since 2002.

In yet another response to a question by Mr. Rahul Kaswan in the Lok Sabha on July 16, 2014 about learning achievements, the government states: “The reasons for low-level achievement include, inter-alia, the non- availability of professionally trained teachers and adverse Pupil Teacher Ratios (PTR) at the school level.” How plausible is this explanation? DISE data indicate that between 2006-7 and 2013-14, there was a net increase of 10 lakh government schoolteachers over and above the previously existing 36 lakh primary and upper primary teachers. So, we have 3.63 lakh new schools sanctioned and 10 lakh new teachers.

So, how adverse is the PTR at this point?

Nationally, DISE reports that PTR has dropped from 36 children per teacher in 2005 to 25 children per teacher in 2013 in primary schools. In upper primary schools, the PTR has dropped from 39 in 2005 to 17 in 2013.

Excepting Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, where PTRs for primary and upper primary are reported to be 38 and 23, and 41 and 34 respectively, every other state has achieved an extremely favorable PTR. The hilly states have one teacher for less than 15 or in some cases 10 children. School by school, there may be variations in the PTRs. But that is a problem for the administration to solve – to ensure that these teachers are properly distributed across schools.

So in reviewing the evidence, it is clear that the MHRD, the SSA, and state governments have done rather well in providing key inputs, building infrastructure and hiring teachers. They focused on it and achieved it.

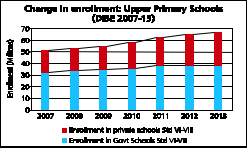

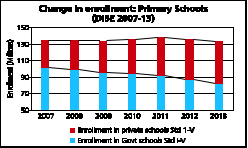

But the paradox of the last 10 years is that while governments spent money on building schools and hiring teachers by the lakhs, and also provided free textbooks, uniforms, and midday meals, the net enrollment in government schools went down and enrollment in private schools went up sharply, especially in the primary stage. Between 2007 and 2013, according to the DISE, total enrollment in primary schools peaked in 2011 at 137 million while the upper primary enrollment grew from 51 million to about 67 million. During this period, enrollment in government schools (Std. 1-8) declined by about 11.7 million, from 133.7 million to 121 million. In contrast, the enrollment in private schools went up by 27 million, from 51 million to 78 million.

There could be several reasons for why parents have been choosing private schools over government schools in spite of free textbooks, uniforms, and midday meals but the government has certainly contributed to this change in a big way by neglecting to act on poor learning levels.

In 2012 the Planning Commission emphasized learning outcomes and things began to change again. The MHRD started talking about learning achievements and NCERT seems to have fallen in line although their reports in the published National Assessment Survey are as opaque as before and only intelligible to experts.

This is the scenario when the new government has taken over. The question again is, what will the strategy of the new government be? The Prime Minister has already declared a goal for toilets in every school. According to ASER 2014, only 6 percent of government schools do not have toilets but an additional 28.5 percent do not have toilets that are usable; 18.8 percent of schools do not have girls’ toilets and 26 percent have girls’ toilets that are not usable or were locked. So, meeting this target should be relatively simple given the Prime Minister’s national-level high-profile thrust.

On the learning achievement side, the new government has continued the policy of focusing on learning achievements but the problem again is one of strategy. Will it again have a linear thrust? The Padhe Bharat Badhe Bharat sub-scheme of the SSA has set an outcome goal of 85 percent children in Std 1 and 2 reaching specified learning indicators in 2016-17. That is two academic years from now. Building the basic foundations well is laudable but what about the older children who have big deficits in basic skills? Is there a good reason why basic learning achievements should not be stressed at higher standards simultaneously?

Currently, in most states, teachers who teach Std 3 to 8 have no clearly stated or focused learning goals to achieve except completing the syllabus. The Right to Education Act, if anyone wants to take it seriously, says it is the duty of the teachers to assess each child’s learning ability and provide additional instruction as required. It also says that an out-of-school child who is enrolled directly to her age-appropriate grade has a right to special training to be “on a par” with other children in the class. The assumption in writing the law was that all children in school have achieved grade-level abilities and that out-of-school children joining these classes will have to catch up. The problem is that the grade-level capabilities are not defined in a measurable way and it is obvious looking at ASER or even NAS results that all children are not at the same level. In fact they are well below what would be expected of them. The government has admitted several times that learning levels are low but there is no measure of how low compared to any set standard. But the idea is quite clear: that those who lag behind have a right to be helped to catch up.

Is it the Ministry’s view that the children in higher grades can read and comprehend what they read? The humiliation of Himachal and Tamil Nadu standing 72nd and 73rd in PISA among 74 participants, higher only than Kyrgyzstan, cannot be forgotten no matter what excuses NCERT came up with.

We live in a country that has achieved near universal enrollment, built enough schools, and appointed teachers and academic support staff. In the same country, we have children in higher grades who cannot read well and cannot comprehend what they read. It is also clearly visible that a large proportion of children are leaving government schools and seeking other options including supplemental help over and above school. It is incomprehensible why governments (past and perhaps the present too) have been unwilling to tackle this learning crisis head on.

Remedial learning is something Indian education experts have frowned on. In the meanwhile, a hundred million children have gone through the schools in the last decade without basic reading and math skills. The experts were busy working out holistic ideals without a clue about how to get them on the ground. The Government of India, under the influence of these experts, took a long time to move to a learning outcomes orientation and stopped well short of what is urgently needed.

It is time to cover the huge backlog in basic skills created by the neglect of at least the last decade. Pratham’s experience is that children in Std 3 or higher can learn to read with proficiency and learn the basics of arithmetic quite quickly. Continuing with reading, writing, thinking and speaking exercises focused on deeper comprehension leads to enhanced levels of confidence and understanding. This helps a child to reach a threshold beyond which she can be a more independent learner, less dependent on the teacher. Or, it may be said that the “chalk and talk” methods can then give way to better teacher-student interactions. A strategy for acceleration of pace in improving learning outcomes across schooling years is urgently needed.

Ground-level evidence shows that the achievement of high levels of reading and math proficiency in Indian schools is not something that should take decades. If we simplify matters and focus on the key areas to build a platform for higher learning, it can be achieved in less than five years within the limits of current human and financial capacities.

The Padhe Bharat Badhe Bharat initiative to create a base for reading, writing, and math fluency is a good step. However, it is yet to be seen if it will succeed as envisaged. Pick-up is quite slow. Given the achievement in hiring teachers and creating infrastructure over the last decade, the Government of India and the state governments are still moving at the old pace of business as usual. Now acceleration is not only possible but also critically necessary.

The child population in India has started to decline and the demography will change dramatically over the next 20 years. Unfortunately, the predominant thinking about India’s economic advance has been and continues to be centered on the investment of financial capital. That limitations of human capital at the base of the pyramid could be a big hurdle in India’s economic advancement is not expressed or felt strongly, either in industry or among policymakers. Perhaps 50 percent of India going to private schools will provide enough human capital for the economic engine. Where is the urgency to get the rest better educated to meet the challenges of the future?

As we complete 10 years of ASER, the Government of India deserves to be congratulated on its achievements in infrastructure over the last decade. The expansion of infrastructure and facilities has led to larger numbers of children transitioning to the upper primary stage and beyond. But its neglect of learning outcomes has definitely contributed to a growing divide in every village and community between those who access private schools or tutors, and those who do not. Further neglect and the slow pace of change will be more disastrous educationally, socially, and politically.

1. CEO-President, Pratham Education Foundation

2. Annual Status of Education Report

3. The United Progressive Alliance (UPA) is a coalition of center-left political parties in India formed after the 2004 general election. One of the members of UPA is the Indian National Congress, whose President Sonia Gandhi is also the Chairperson of the UPA.

4. The National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) is an organization set up by the Government of India, to assist and advise the central and state governments on academic matters related to school education. It was established in 1961.

5. District Information System for Education

6. The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) is a worldwide study by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in member and non-member nations of 15-year-old school pupils’ scholastic performance on mathematics, science, and reading.