One of the first questions to address when approaching the gap between secondary and higher education in the Arab World is whether this gap is a reality or a myth. In the last few years, I was particularly intrigued by this question, which led me to conduct a sample study including 2500 GCC students sent abroad by our organization to pursue a higher education degree. Through the analysis of their secondary education data, I was able to conclude that the gap in question does in fact exist not only on the level of the GCC countries but also across the Arab World in general. In fact, even though the sample was essentially made of grade twelve GCC students, students in question were not formed by GCC school systems only: many of them, though currently living in Gulf countries, came from other Arab nations or attended international schools in the region.

What does the K12-Higher Education Gap look like? This gap is signified by a mismatch between the skills and knowledge K12 graduates acquire and those required by Higher Education Systems locally, regionally and internationally. It is visible through various shortages in the skills and competencies acquired by school graduates throughout secondary learning.

K12 graduates do not only lack some of the elementary hard skills taught in schools, but they also show serious deficiencies on the level of soft skills as well. Throughout my professional field observations, I was able to perceive a flagrant insufficiency in students’ tertiary learning skills.

These insufficiencies are visible on the level of language, communication and writing skills especially in foreign languages like English for example. Students also show a low participation level in their community and a deficiency in international educational or life experience due to lack of interest or opportunity.

Similarly, students score low on math and sciences, and fall short on research skills competencies. But most importantly, graduates are uncertain about their choices of future career or field of study: they lack serious information about university admission pre-requisites (like SAT, TOEFL or IELTS), they find it difficult to write their essays and personal statements, and have no skills for interviews. According to research results, these deficiencies are further accentuated when students originate from public schools systems where acquired English skills are remarkably lower and career counselling or guidance is highly limited.

Research outcomes clearly indicate that, following their graduation, secondary education students are not sufficiently equipped to directly join higher education institutes and universities. An intermediary phase or conjunction is crucial to ensure they develop the required pre-requisites and skills necessary for their future success. As a result, students often waste an additional year either studying English, taking university preparation courses, or preparing for their SATs.

Once the existence of this gap established, it is only logical to question the reasons that lie behind it. The question “Why is there a gap between K12 and Higher Education in the Arab World in general and GCC countries in particular?” becomes even more curious when we take under consideration the increase in the expenditure on education in the GCC countries. In fact, GCC states spend relatively high amounts of their GDPS (4-5%) on the education sector, which is expected to play an integral role in the future economy of the region. In fact, an average of $150 billion is invested in education on a yearly basis; still students are lacking the basic skills to enter higher education establishments. So where does the flaw reside and what are the real roots of this mismatch?

Many essential pillars of the education process can be identified, and each one of these pillars can be questioned about his or its share of the responsibility in the permanency of the current situation. Students, parents, teachers and even governments share a common obligation towards ensuring the quality of education students access and acquire throughout their secondary years.

On one hand, students and parents should be held accountable towards themselves. Students ought to be motivated and pursue the opportunities to attain, retain and develop the skills required by universities and the job market; while parents should ensure they are well informed about the market state and condition to become actively and positively involved in the career guiding and counseling of their children.

On the other hand, teachers and governments should also fulfill their share of the bargain. Teachers are to make sure they are equipped with the best 21st century teaching methodologies. They should undergo frequent training and career development programs in order to maintain the necessary motivation, passion and skills for a successful teaching career. Governments on the other side have a double role to play: the first is to monitor the quality of education within the various certified schools, and the second is to establish public-private partnerships to ensure the contribution of the private sector in the curriculum and student building process.

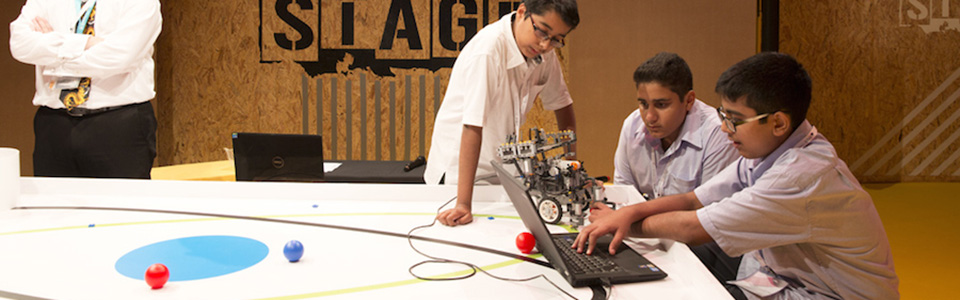

Many studies have been focusing on the 21st century requirements or skills. These requirements are defined according to common problems faced by most of the world countries. Twenty first century skills fall into three main categories: foundational literacy skills, general competencies and character-building qualities (Hilton and Palligreno, 2012). What is most astonishing is that graduates from the region are scoring low on every one of these three categories as they seem to be lacking literacy and numeracy skills, scientific literacy skills, ICT literacy skills, financial literacy skills and cultural and civic literacy skills! As for general competencies, students lack critical thinking and problem solving, creativity, communication and collaboration skills. Students also do not manifest curiosity, initiative, persistence, grit, adaptability, leadership and social or cultural awareness.

There are over 600 schools in the UAE, 300 in Qatar, 240 in Bahrain and many more in KSA, Kuwait and Oman. At Education Zone, we are very interested in collecting information about the education systems each of these schools apply. This knowledge allows us to observe and analyze the skills students are fostering within the different systems and match them to the skill set generally required from students by the time they reach tertiary education levels. Throughout our research, we concluded that the persistent gap in the education systems in the Arab World and GCC in particular can be closed through the introduction of new teaching models. The Rudolf Steiner German system is a typical example of new innovative systems that allow students to successfully attain and foster 21st century skills.

As GCC governments continue to invest in the reform of their education systems, it is time to realize that we will not achieve any return on investment unless we tackle the real and actual system shortages. I am sure we all agree that our children deserve better.