The future of learning is here before we know it. The COVID-19 social distancing measures resulted in many education systems having to shut down their facilities and move learning and instruction online. While a three-way blend of technology, internet, and education presents an enormous opportunity for education systems to embrace the future, there is a real risk of channeling learning opportunities through already-existing forms of digital disparity, especially for marginalized populations.

Globally more than 188 countries implemented country-wide school closures and 9-in-10 learners were affected. In times of crisis, as with the COVID-19 pandemic, lack of equitable learning opportunities will hit the most vulnerable the hardest.

The academic literature on digital learning supports the view that tech literacy and connectivity are essential for the future of learning. Yet access to this technology and digital content remains unequal within and across regions. While this challenge can be addressed by supporting schools with more resources, limited digital access at home can compromise such efforts. Studies show that differences in family socioeconomic conditions, home connectivity, geography, etc. contribute substantively to an expanding digital divide that segregates the haves and have-nots in this digital age. If unequal access to technology is left unaddressed, the global impact on student learning will be devastating. Education systems have a critical role to play in addressing this digital divide, especially during pandemic-led school closures.

China, as one of the first education systems to experience system-wide school closures due to COVID-19, has a significant digital divide, which limits the full potential of online instruction. Let’s have a look at the most recently available data: Of the 12,058 Chinese students (B-S-J-Z regions) surveyed in the 2018 wave of Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), 71% did not own e-book readers, 36% reported not having a tablet computer at home, and 20% did not have access to an internet-capable computer at home. Although this sample of students was taken from China’s most developed provinces, we see vivid signs of digital disparity.

How did China address the digital divide during the COVID-19 school closures?

To examine the ramifications of the digital divide on learning in real-time, and the policy measures put in place to mitigate this, my research group began tracking the national- and provincial-level COVID-19 education response in China since the initial outbreak.

We identified three compelling takeaways:

1. A concerted policy response from national and local education authorities

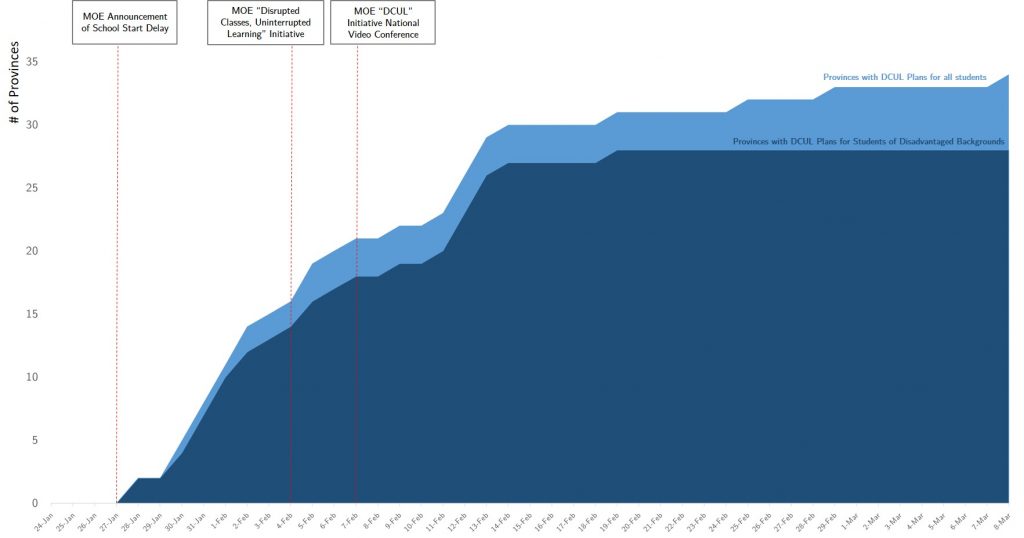

National education authorities in China announced postponing schools early on during the initial outbreak (see Figure 1). There was a joint response from both national- and local- education authorities, which ensured that by mid-February, more than 30 provinces had published localized versions of the national “Disrupted Classrooms, Uninterrupted Learning” (DCUL) education plan, for schools, teachers, and students. While the national DCUL guidelines covered broad policy principles and standards, provincial versions were encouraged to be differentiated by local context, and designed to be practice-oriented with detailed protocols, resource contacts, and FAQ information.

Figure 1. Timeline of COVID-19 Education Response among Chinese Provinces

Source: Author’s compilation

2. Contextualized action plans offering alternatives to online education

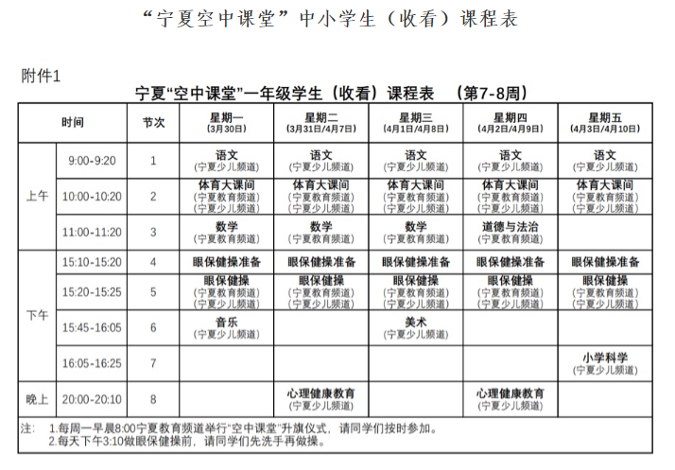

A majority of the localized provincial-DCUL education plans included a designated section focusing on students from disadvantaged backgrounds. For instance, in Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, a self-governing Muslim majority province in Northwest China, local education authorities worked with major telecommunication carriers to waive cellular data and internet usage fees for students and families from remote and low-income communities. This policy priority made their participation in synchronized online classrooms possible. In addition, TV and radio stations coordinated to broadcast “Classrooms on Air” content via satellite. This measure aimed to ensure that pre-recorded educational material reached rural students where cellular towers do not. Classrooms on Air is streamed five days a week, 9 am to 8 pm, with an array of 20-minute-long lessons. Content includes both grade-specific instructional lessons such as language studies and mathematics, as well as crisis-relevant educational content such as psychological well-being and at-home exercises (see Figure 2 for an example of a broadcast timetable).

Figure 2. Example of Ningxia “Classrooms on Air” Lesson Timetable

Source: Ningxia Public Service Platform for Educational Services

3. Cloud-based resource pooling strategies to support teachers and students

Cloud resources were quickly mobilized by both public and private sectors to support teachers and students. For example, National Public Service Platform for Education Resources (EDUYUN) made e-versions of textbooks and instructional toolkits publicly available, covering a wide range of subjects and grade-levels. In addition, EDUYUN initiated a lesson plan and instructional resource sharing platform where teachers could upload, review, and discuss lesson planning materials. Furthermore, local education authorities partnered with private-sector tech companies to expand online instructional capacity and to provide better online learning experiences for students. For instance, Tencent Classroom and Rain Classroom collaborated with more than 40 municipal education bureaus to offer live and recorded lessons, with a variety of attendance, assessment, and interactive classroom tools that can enhance student learning experiences.

As the global community unites and continues our common fight against COVID-19, we must not forget that education systems need to respond to school-closures in equity-meaningful ways. The effects of the digital divide on learning can only be addressed if we start treating education inequality seriously, both online and offline.

The future of learning has arrived quicker than expected, amplifying already-existing inequalities and limiting education from fulfilling its promise to learners worldwide. China’s early intervention and experience may prove to be useful as we tackle the digital divide with determination and rigor to ensure that the future of learning is undivided for all.