Sustaining continued learning has become one of the main/urgent developments in education as the global pandemic continues to unfold. We as resilient human beings must seek ecosystem-based approaches to change adaptation. To start, we must ask ourselves “are we ready for such change?”

Being ready to adapt ecosystem-based changes for sustained learning requires us to understand what it means to become a ‘learning ecosystem’ for the future, how we know our level of development, and what we need in order to get there. The future learning ecosystem reflects a system of systems in which each component and agent of the system working independently and collectively to provide a curated continuum of learning that is lifelong, tailed to individuals, accessible to all that are across sectors, diverse locations, channels, and periods of time. Developing and maintaining such a learning ecosystem represents an enormous undertaking, as its many subsystems or agents must evolve in concert. As such, understanding the linkages that connect parts of a system and its resulting coherence is key to an effective learning ecosystem. One of the oft-used strategies to assess the level of system coherence is to examine the degree of health for the ecosystem network which includes a self-diagnosis tool and measures of systems’ network health.

The self-diagnosis tool can be found in several forms such as self-administered or self-initiated online measurement tool, support from external evaluators or consultants, etc. For instance, one of the self-initiated/administered tools that has gained much traction is the initiative proposed by Jordi Díaz Gibson and Alan J. Daly in the previous article in this special focus. They proposed the use of the online School Weavers Tool in response to the NetEdu global movement. The Tool allows individual schools to assess their degree of systems health through a set of scientifically proven concepts that are influential indicators of systems health such as supportive climates, innovation and collaboration, and a strong focus on inclusion and individual development.

Take ‘collaboration’ as an example. The Tool asks school members (administrators, teachers, students, classified employees, and family and community partners) to assess three aspects of collaborative climate on a five to six Likert-type scale:

1. individual-level collaboration: the degree to which members are working collectively in improving student learning (sample question: ‘Teachers collaborate with each other;

2. community-level collaboration: the degree to which schools make an effort to work with other schools, family, and community partners to meet the learning needs of students (sample question: ‘My school makes an effort to reach out to the community); and

3. resources supportive of collaboration: the extent to which resources (time, personnel, training, funding, etc.) are provided to facilitate collaboration at both levels (sample question: ‘Time and resources are provided to facilitate collaborative work’). Items or aspects with rating scores lower than the overall school mean or lower than the expected performance are those areas in need of improvement.

One of the unique features of this tool is the ‘weaving’ component, which refers to the opportunities for schools to not only share their educational practices (success stories, issues, or challenges) but also exchange insights with other school systems across the globe that are also using the tool. In turn, schools would be able to make informed decisions for improvement based on the assessment results. In other words, results from the tool can also be indicative of an individual school system’s health level. For any weaknesses spotted, schools would be able to access and mobilize the resources shared by the ‘weavers’ across the larger global pool of expertise for improvement.

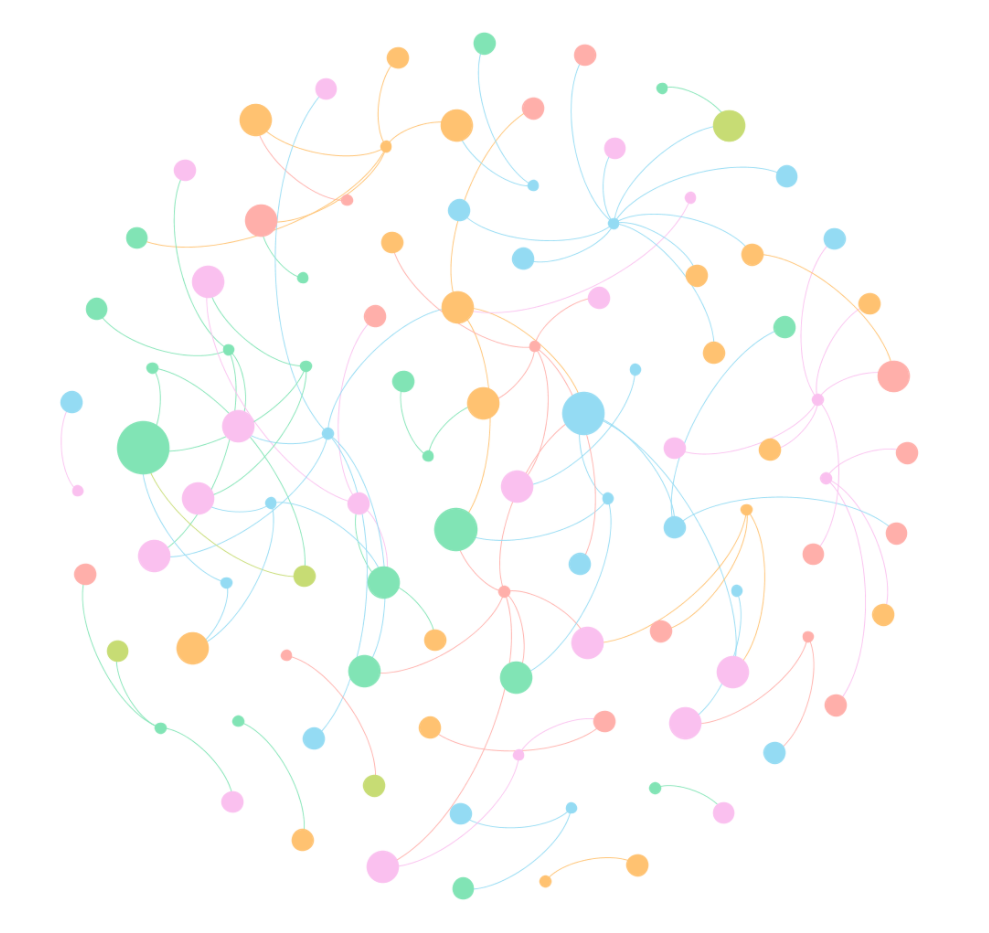

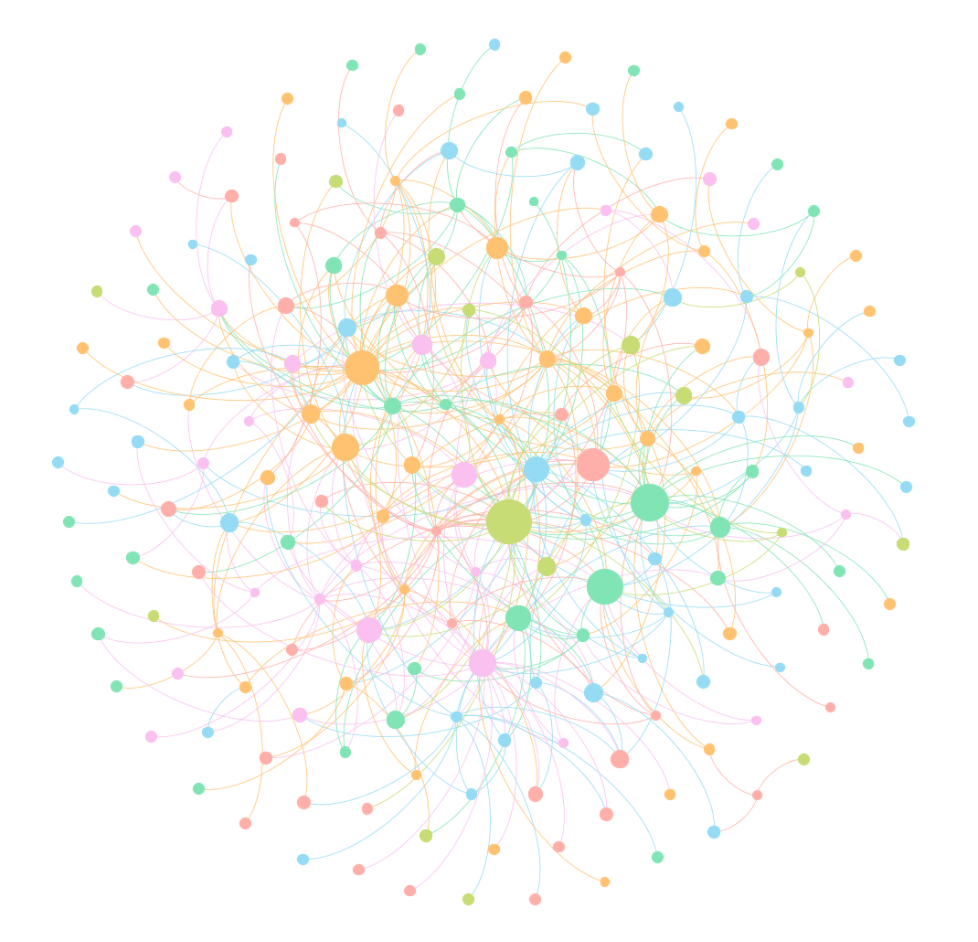

In terms of assessing systems’ network health, a growing body of research communities in improvement science and public administration has called for a network approach to systemic change and improvement (Russell et al., 2017). The idea is to assess the quality (coherence) of relational patterns between/across components of a system and whether these patterns are supportive of the network’s goal(s). Take one of our studies as an example (Liou & Daly, 2020). Figures 1 and 2 represent networks of a regional STEM ecosystem that aims to provide STEM-related learning pathways for individual learners. The ecosystem consists of actors from six different stakeholder groups (school districts, institutions of higher education, museums/zoos/libraries, businesses, government, and community-based organizations) working to build strategic collaborative relationships with one another. Nodes are colored by these groups and sized by the degree of connectivity (the larger the node the more active the node). Figure 1 shows the collaborative relationships existing within each sector, whereas Figure 2 shows the inter-sector relationships. The patterns of both networks suggest a strong orientation toward collaboration between sectors, which is one of the goals of this STEM ecosystem. However, its less well-connected within-sector ties may be an area of improvement should the ecosystem attempt to also facilitate growth for individual districts, institutions, or organizations. For school systems aiming to create a cohesive network in a learning ecosystem, one of the strategies is to develop a ‘network initiation team’ including key actors that are social influencers, movers, and shakers to help bridge connections and spread key information and resources throughout the system and across different stakeholder groups.

Figure 1: The STEM ecosystem’s intra-sector network of strategic collaboration relationship

Figure 2: The STEM ecosystem’s inter-sector network of strategic collaboration relationship

Several common challenges faced by many schools and practitioners in Taiwan and other countries/areas when administering assessment of systems health are time, resources, and commitment. Time and resources have always been the initial responses we received as hurdles for change implementation. The school system needs to create a social infrastructure supportive of change endeavors, whether it involves time, personnel, funding, etc. If people are expected to make changes, they will need the necessary resources to do so. The system needs not only to support the change efforts but also to facilitate the overhead required by the change process. Commitment to change is another common challenge. It requires a demonstration of ‘skin in the game’, i.e., buy-ins from individuals and each organization and stakeholder group. They need to understand why the change needs to take place, why it will help them personally and collectively, and how it will be implemented and/or integrated within existing systems. A compelling vision of and rationale supporting what the school system would look like in the shape of a future learning ecosystem helps generate the buy-in and efforts needed to implement change.

Never before have we experienced such far-reaching implications due to a common global threat to our health and learning systems. Realizing the concept and architecture of our future learning ecosystem is powerful and will extensively affect how we think, live, work, and learn. Such systemic impact cannot be achieved without a clear and shared vision, resources, commitment, and networked coordination. Bringing together teams of collaborators with various areas of expertise in the shape of networks is key for achieving the full potential of the learning ecosystem.